Avoidant behaviour can be frustrating for both the person and those around them.

How can we improve our relationship with others and ourselves, so we can build better quality relationships with others?

This blog delves into my personal experience of being on the dismissive avoidant spectrum, how avoidant attachments can develop and provides a few tips for how to move from avoidant attachment styles to secure attachments.

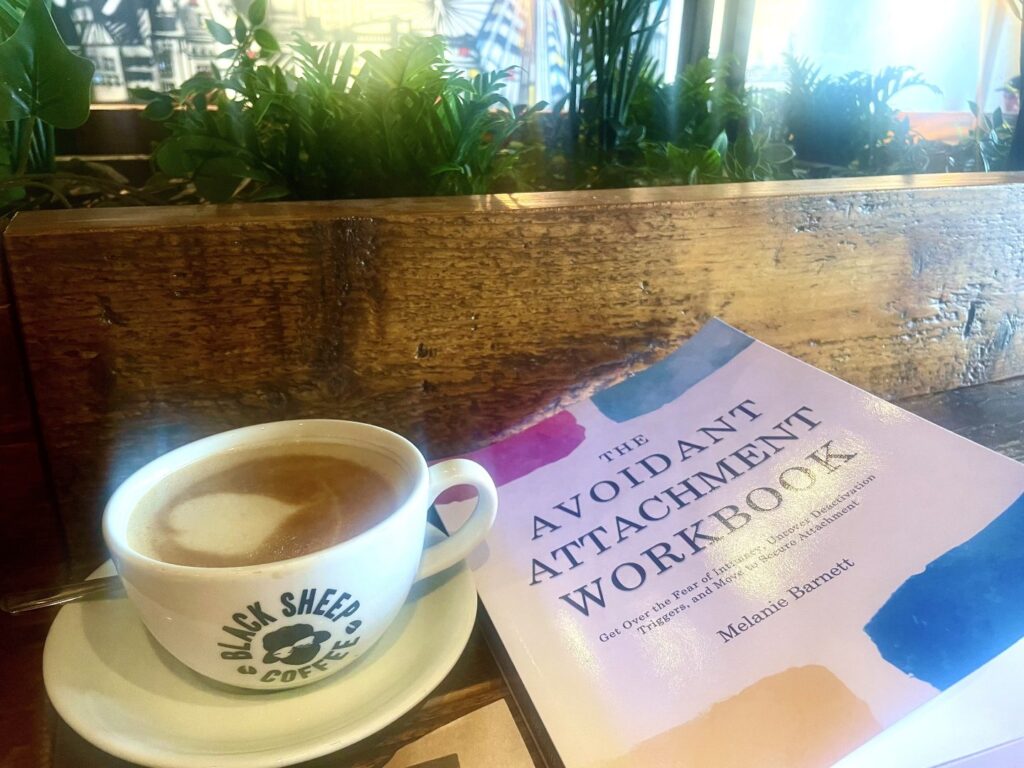

Incidentally, I have been working through this brilliant workbook. It has a huge amount of information about avoidant attachment styles: their roots, and the effects that they can have on your relationships. I will be quoting from this book a few times in this blog.

Most importantly, it can help you build towards a more secure attachment style by facilitating a journey of self-discovery with questions targeted towards the avoidant (some of these are challenging).

What is Attachment Theory?

Attachment theory is a psychological framework for understanding the relationships between people.

The theory itself was developed by John Bowlby. He became interested in child development, in particular, the effects that separation from the caregiver has on the child.

There are four attachment styles: secure, avoidant, ambivalent and disorganised.

From my reading so far, it appears that attachment styles are not fixed, and are not mental disorders. They are models for the patterns of behaviour that people exhibit in their relationships. This means that someone can develop and grow from one attachment style to a more secure style.

The Avoidant Attachment style is split into three subtypes:

- Avoidant Dismissive

- Anxious Avoidant

- Fearful Avoidant

In this blog, I will concentrate mainly on the avoidant dismissive, as I have insight into this area.

Avoidant Dismissive Attachment

When I look back on my childhood, I believe it was happy, and it is difficult to pinpoint where my dismissive tendencies have their roots.

I suppose there are many societal factors too, which lead men in particular to develop more dismissive avoidant tendencies.

For instance, we often say these things to boys: “Boys don’t cry”, “You’re too sensitive”, “because I said so”, etc.

These phrases have the impact of invalidating boys’ feelings and making it seem like their negative emotions don’t matter.

Other roots of dismissive avoidant attachment are emotional neglect as a child.

What is the net impact of this?

- Dismissive avoidants are less aware of their emotional states

- They tend to be extremely independent – taking care of their emotional needs (co-regulations)

- They tend to dismiss the emotional problems of others

- Fixate on a past partner (who is their perceived ideal)

- They often have high confidence in their practical abilities

- They confront problems with their intellect rather than rely on an emotional toolkit

- Have low self-esteem – they feel like they don’t belong or walk the world alone. Their value is linked to external or materialistic things

- Think others are incompetent unless that person is their “ideal“

The Dismissive Avoidant vs the Narcissist

Overall, the dismissive-avoidant probably encounters the most stigma. Being in a relationship with an avoidant-dismissive can feel like being in a relationship with a narcissist.

An avoidant dismissive can sometimes seem to “gaslight” a partner, just like a narcissist. For instance, if a partner says that he/she feels upset because of something, the avoidant dismissive could say, “That’s not a big deal” just like a narcissist would. These words can often leave a partner feeling like their feelings are not important or valued.

The dismissive-avoidant and narcissist, however, differ in terms of their intentions. A narcissist will say something to injure a partner and gain control.

On the other hand, a dismissive avoidant will say something like this because he/she doesn’t comprehend the value of these negative emotions. Your shadow self lies at the heart of this and requires acknowledgement.

In most cases, they would not want to injure the other person, but would rather be hoping to move to resolution.

As a dismissive avoidant has the unique ability to coregulate their own negative emotions and somehow believes that everyone else should be able to do this on their own.

My Own Experiences

I have always found it difficult to feel connected to negative emotions. I am aware that I may be experiencing anger, guilt, grief, etc., but there is a barrier that acts to numb me from those feelings. In some ways, it is a great comfort and makes me feel almost impenetrable.

This barrier likely developed as a defence mechanism to protect myself from the intensity of negative emotions. It serves to keep me from becoming overwhelmed, but it also prevents me from fully processing these emotions.

Sometimes when I’m down, I paradoxically smile and laugh. When I think about or talk about traumatic events, I sometimes can’t help but infuse everything with humour. This reaction is another layer of my defence mechanism.

By turning to humour, I can create distance from the pain and present a more controlled, composed exterior. However, while humour can diffuse tension, it may also prevent me from acknowledging and addressing the underlying hurt.

Ultimately, my whole life, I have feared being seen as weak or vulnerable. Potentially a source of this insecurity stems from the bullying I experienced as a child. Being vulnerable made the bullying worse, and it was when I punched the bully that things became better.

This experience may have taught me that strength, or at least the appearance of it, could protect me from harm. Consequently, I learned to equate emotional expression with weakness and to value stoicism of as a means of self-preservation.

Appearing strong, therefore, gave me greater value than showing my negative emotions. I internalised the belief that vulnerability is dangerous and that strength lies in emotional suppression. This coping strategy became ingrained, shaping my interactions and emotional responses.

I remember when my grandfather died, I made a conscious effort not to be weak and cry. I wanted to be strong for others in my family experiencing grief.

At that moment, I prioritised their needs over my emotional expression, believing that showing strength would provide support. However, this self-imposed emotional restraint likely limited my ability to fully grieve and connect with others during a time of shared loss. It reinforced the notion that being strong means suppressing my pain for the sake of others.

Moving Towards Secure Attachment

The crucial first step to achieving a more secure attachment is discovering that you have a problem. This is a bit like an addict admitting that they have a problem.

You can easily take an assessment test to explore your attachment style here.

When I discovered my attachment style, I was able to start taking specific actions and resolve some of my issues.

After that, spend some time meditating and attempting to connect with your emotions. This will take time and effort. Journalling can also be an extremely useful tool for you to employ.

Next, you need to think about relationships, both current and past. Recognise those moments where you were dismissive of other peoples’ feelings and needs. Then you need to spend time delving into why you were dismissive. Self-introspection and analysis are critical to growth.

Fourth, spend time learning how to listen to other people (even strangers) talking about their difficult problems and emotions. Rather than suggesting solutions, attempt to focus your energy on empathising with them. This will be uncomfortable at times but will help you develop some emotional tools which will allow you to tackle relationship issues more effectively.

Think about it this way, if you can try to talk, and focus on the feelings of someone else, who has less meaning in your life, you’ll be more present for those who matter the most to you.

Fifth, cultivate a positive self-view of yourself by challenging your deep-seated insecurities. You may need to talk to a therapist.

Finally, seek attachments with others who are experts at cultivating healthy relationships. They will help you understand your emotions better and be able to offer advice.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this blog has explored my journey as a dismissive avoidant, the development of avoidant attachment styles, and strategies to transition towards secure attachments.

Through personal anecdotes and insights from a valuable workbook, I’ve shared how understanding and addressing these attachment patterns can lead to healthier relationships.

By recognising the problem, engaging in self-reflection, and seeking supportive relationships, anyone can move towards a more secure attachment style. Embracing vulnerability and empathy are crucial steps on this transformative path.

thanks for info.